Shaping Symbioses

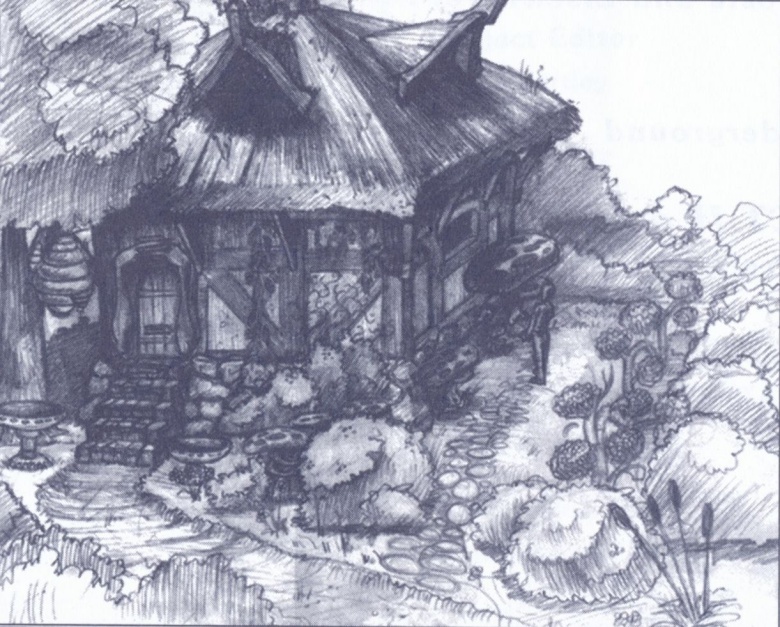

Concept art for the Dungeon Master's Lair, Zork Grand Inquisitor.

Humans tend to see objects as the building blocks of reality: walls, chairs, windows, computers, trees—things they can pick up, point to, buy, sell, and throw at each other. They carve reality up into isolated bits, hoping to understand and control each piece in isolation. Sometimes this approach is useful. But to focus on trees is to misunderstand the forest, and humans are all too prone to the particular type of misunderstanding that comes from focusing too narrowly.

By contrast, an elven view of reality pays more attention to the relationships between things, even going so far as to acknowledge that many of the thing-like concepts in our experience are constructed entirely of such relationships.

For instance, the concept of "home". What do we mean when we say home? Home tends to be located in a physical structure, the way consciousness tends to be located in our physical brains, but when we say "home" we aren't generally referring to something physical. Home doesn't just mean shelter. A shelter might not be anyone's home, and someone's home might not be a shelter.

Rather, it seems to be a particular kind of relationship between shelter, a person, their family, and their daily travels. There's an emotional connection involved, and a sense of roots and recurrences.

We can go a level deeper and examine the concepts of which home is composed. Family is another system of relationships. How about "shelter"? A relationship between physical matter and space, in the context of a particular climate...

Over and over, I've seen that when people care enough about an object to name it with words, it has this structure, of relationships within relationships. The deeper the network of nested relationships is, the more emotionally connected people feel to the object.

Dirt, rocks, and plant matter. Not a garden.

As a more concrete example, take the idea of a garden. One way of looking at it is to say a garden is made of plants and soil and stones and walls. But a garden is not just those things: not any arrangement of soil and plants can be called a garden. In a garden, there are particular relationships between the plants and soil and rocks and so forth, and these are what actually make the garden a garden. The relationships and arrangements are actually more important than the physical matter: you can make a kind of garden without plants, by arranging rocks and gravel, but just try making a garden out of plants (or anything else) with no arrangement!

A room, a class, a university, a nation, a company, a friendship, a meal, a game, a doorway, a story, a fire, a drink, the Internet: they're all relationships. Each of these "things" is really a pattern of interactions of many other things, each of which is itself a set of relationships...

Atomic Relationships

If you keep analyzing the relationships in a concept at finer and finer levels of detail, eventually you get to a point where the relationship is unanalyzable. These "atomic relationships" are the distinctions that have no substance or meaning other than their existence as a distinction. In the following sections, I describe a few everyday situations where the atomic relationships show themselves.

It's interesting that these fundamental units of reality, whether in the "subjective" or "objective" domains, are always relationships, and never objects.

Typography

Computer Science

Computers do everything with binary numbers—all data is processed as a sequence of zeroes and ones. This is because it's easier to build circuitry when you only have to distinguish between two possible values at any one moment.

But have you ever wondered: from a computer's-eye view, what is a zero or a one? What are they actually made out of? The answer is... it depends. In some situations the difference between a zero and a one might be distinction between a low voltage and a high voltage on a wire. Sometimes it might be the polarity of a magnetic domain on a piece of metal. Sometimes it's a pattern of radio waves.

The meaning of the zeroes and ones doesn't come from their physical medium. Even the specific representations within a medium are merely conventions: though it seems natural in some sense to represent zero by a low voltage and one by a high voltage, we could just as easily choose the opposite representation if that was more convenient for some reason. The only important thing is the existence of the distinction.

This page is still under construction. I'll have the rest of it up shortly!